The past, present and future of virtualization

Let's have a look at the current dominant solutions in cloud virtualization in terms of how they originated and have spread in the last years, along with future directions.

The following article is a brief summary of the past, current and future trends in system virtualization. The papers as source are linked at the end of the page.

The rapid pace of innovation in datacenters and the software platforms within them has transformed how companies build, deploy, and manage online applications and services. Until the last decade, basically every application ran on its own physical machine.

The high costs of buying and maintaining large numbers of machines, and the fact that each was often under-utilized, led to a great leap forward virtualization.

Virtual Machine Monitors (VMM), born at the end of the 1960s, went back to being popular in the late 2000s and they enabled tremendous consolidation of services onto servers, thus greatly reducing costs and improving manageability. However, hardware-based virtualization is not a panacea, and lighter-weight technologies arised to address its fundamental issues.

One leading solution in this space is containers, a server-oriented repackaging of Unix-style processes with additional namespace virtualization. Combined with distribution tools such as Docker, open-sourced in 2013, containers enable developers to readily spin up new services without the slow provisioning and runtime overheads of virtual machines, at the cost of less resource isolation.

Common to both hardware-based and container-based virtualization is the central notion of a server and servers are notoriously difficult to configure and manage. As a result, a new model, called serverless computation, is poised to transform the construction of modern scalable applications. Instead of thinking of applications as collections of servers, developers instead define applications with a set of functions with access to a common data store.

Existing serverless platforms such as Google Cloud Functions, Azure Functions and AWS Lambda isolate functions in ephemeral, stateless containers. The use of containers as an isolation mechanisms causes however latencies up to hundreds of ms, which may not be acceptable for some applications or for devices operating ad the Edge of the network. Besides containers have a not negligible resource footprint and isolation issues.

The following sections offer a history of the past and current trends of the different virtualization techniques.

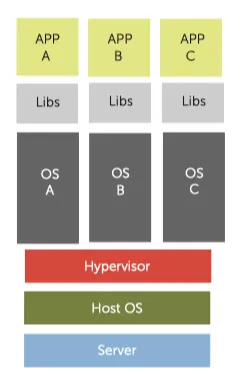

VM

At the end of the 1960s, the VMM, also called a hypervisor, came into being as a software-abstraction layer that partitions a hardware platform into one or more virtual machines. Each of these virtual machines was sufficiently similar to the underlying physical machine to run existing software unmodified.

At the time, general-purpose computing was the domain of large, expensive mainframe hardware, and users found that VMMs provided a compelling way to multiplex such a scarce resource among multiple applications.

The 1980s and 1990s, however, brought modern multitasking operating systems and a simultaneous drop in hardware cost, which eroded the value of VMMs. As mainframes gave way to minicomputers and then PCs, VMMs disappeared to the extent that computer architectures no longer provided the necessary hardware to implement them efficiently. By the late 1980s, neither academics nor industry practitioners viewed VMMs as much more than a historical curiosity.

In the 1990s, Stanford University researchers began to look at the potential of virtual machines to overcome difficulties that hardware and operating system limitations imposed: this time the problems stemmed from massively parallel processing machines that were difficult to program and could not run existing operating systems. With virtual machines, researchers found they could make these unwieldy architectures look sufficiently similar to existing platforms to leverage the current operating systems.

Furthermore the increased functionality that had made operating systems more capable had also made them fragile and vulnerable. To reduce the effects of system crashes and breakins, system administrators had resorted to a computing model with one application running per machine. This in turn increased hardware requirements, imposing significant cost and management overhead. Moving applications that once ran on many physical machines into virtual machines and consolidating those virtual machines onto just a few physical platforms increased use efficiency and reduced space and management costs without compromising security.

Moving forward however, a VMM nowadays is less a vehicle for multitasking, as it was originally, and more a solution for security and reliability. Functions like migration and security that have proved difficult to achieve in modern operating systems seem much better suited to implementation at the VMM layer.

For instance, AWS runs serverless functions in Linux containers inside virtual machines, with each virtual machine dedicated to functions from a single tenant.

KVM (Kernel-based Virtual Machine) is an example of hypervisor built into the Linux kernel that allows a host machine to run multiple, isolated virtual machines. QEMU is a user-level full-system emulation platform and provides memory management, device emulation, and I/O for guest virtual machines. Due to the emulation being performed entirely in software, it is extremely slow, thus QEMU uses KVM as an accelerator so that the CPU virtualization can happen at kernel level. The KVM/QEMU combination provides each guest with private virtualized hardware, such as a network card and disk. On this platform, most operating system functionality resides in the guest OS running inside a virtual machine.

KVM/QEMU is used for full-system virtualization and in Infrastructure-as-a-Service clouds (Iaas). With IaaS, rather than thinking of any computer as providing a particular fixed service, system administrators view computers simply as part of a pool of generic hardware resources.

However, KVM/QEMU virtualization is heavyweight, due to both the large and full-featured QEMU emulation process and to full OS installations running inside virtual machines. As a result, it is too costly to run individual functions in a serverless environment.

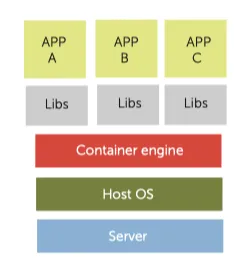

Containers

Linux Containers (LXC) are an OS-level virtualization method for running multiple isolated applications sharing an underlying Linux kernel. A container consists of one or more processes, with reduced privileges, having restricted visibility into kernel objects and of host resources.

Visibility into kernel objects is governed by namespaces, which prevent processes in one container from interacting with kernel objects, such as files or processes, in another container. Resource allocation is governed by cgroups (control groups), provided by the kernel to limit and prioritize resource usage.

Some trace inspiration for containers back to the Unix chroot command, which was introduced as part of Unix version 7 in 1979. In 1998, an extended version of chroot was implemented in FreeBSD and called jail. In 2004, the capability was improved and released with Solaris 10 as zones. By Solaris 11, a full-blown capability based on zones was completed and called containers. As Linux emerged as the dominant open platform, replacing these earlier variations, the technology found its way into the standard distribution in the form of LXC.

With containers, applications share an OS and as a result these deployments will be significantly smaller in size than hypervisor deployments, making it possible to store nowadays a few thousand containers on a physical host (versus a strictly limited number of VMs).

Docker

Docker, open-sourced in 2013, is an extension of LXC that adds a user-space Docker daemon to instantiate and manage containers. The daemon can be configured to launch containers with different container engines, such as the the default runc engine or the gVisor wrapper runsc (gVisor is presented later). The runc engine enables isolation for a running container by creating a set of namespaces and cgroups.

Docker can also initialize storage and networking for the container engine to then use. The storage driver provides a union file system, using the Linux kernel, which allows sharing of read-only files. Files created inside a Docker container are stored on a writable layer private to the container provided through a storage driver.

Each container has its own virtual network interface. By default, all containers on a given Docker host communicate through bridge interfaces, which prevents a container from having privileged access to the sockets or interfaces of another container. Interactions between containers are possible through overlay networks or through containers’ public ports.

Image-based containers package applications with individual runtime stacks, making the resultant containers independent from the host operating system. This makes it possible to run several instances of an application, on different platforms. Many leading cloud providers like Amazon, Google, Microsoft, IBM and others use this technology for enabling Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS), and Function-as-a-Service (FaaS) in the recent year .

Software developers tend to prefer using PaaS compared to Iaas, focusing on developer productivity rather than managing the infrastructure layer. PaaS focuses on providing language runtime and services to developers leaving infrastructure provisioning and management to the underlying layer. Therefore since PaaSs use containers for their runtime, as PaaSs gained in popularity in the last years, so did containers.

Containers are lightweight when compared to virtual machines: they provide extremely fast instantiation times, small per-instance memory footprints, and high density on a single host, among other features. On the downside, containers offer weaker isolation than VMs, to the point where containers are ran in virtual machines to achieve proper isolation.

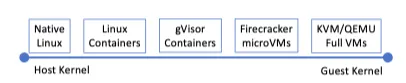

Accordingly, recently lightweight isolation platforms have been introduced as a bridge between containers and full system virtualization.

A bridge between containers and VM

Both Firecracker and gVisor rely on host kernel functionality. Firecracker provides a narrower interface to the kernel by starting guest VMs and providing full virtualization, whereas gVisor has a wider interface by being paravirtualized. They both have low overhead in terms of memory footprint.

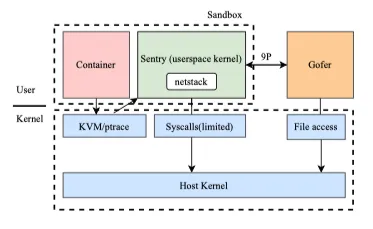

gVisor

In May 2018, Google open-sourced gVisor, a sandboxed container runtime that uses paravirtualization to isolate containerized applications from the host system without the heavy-weight resource allocation that comes with full virtual machines. It implements a user space kernel, Sentry, that is written in the Go Language and runs in a restricted container. All syscalls made by the application are redirected into the Sentry, which implements most system call functionality itself and makes calls to a limited number of host syscalls to support its operations. This prevents the application from having any direct interaction with the host through syscalls.

gVisor has its own user-space networking stack written in Go called netstack. Sentry uses netstack to handle almost all networking rather than relying on kernel code that shares much more state across containers.

Unlike a VM which requires a fixed set of resources on creation, gVisor can accommodate changing resources over time, as most normal Linux processes do, and has flexible resource footprint and lower fixed cost than a full VM. However, this flexibility comes at the price of higher per-system call overhead.

Google currently uses gVisor in Google Cloud Platform (GCP) services like the App Engine standard environment, Cloud Functions, Cloud ML Engine and Cloud Run.

Firecracker

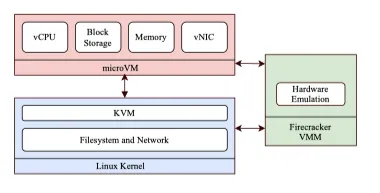

In late 2018, Amazon Web Services introduced Firecracker as a new virtualization technology that uses KVM to create and run virtual machines. Like QEMU, it uses the KVM hypervisor to launch VM instances on a Linux host and with Linux guest operating system.

Firecracker has however a minimalist design and provides lightweight virtual machines called microVMs. It takes advantage of the security and workload isolation provided by traditional VMs but with much less overhead via lightweight I/O services and a stripped-down guest operating system.

Firecracker excludes unnecessary devices and guest-facing functionality to reduce the memory footprint and attack surface of each microVM. Compared to KVM/QEMU, Firecracker has a minimal device model to support the guest operating system and stripped-down functionality. Both of these characteristics allow it to make fewer syscalls and execute with fewer privileges than KVM/QEMU.

Firecracker also adds constraints on the values allowed as arguments to system calls as well. A syscall is blocked if the argument values do not match the filtering rule. Besides, it provides virtual resources and IO and, to ensure fair usage of resource, it enforces rate limiters on each volume and network interface, which can be created and configured by administrators.

Firecracker is currently used by Amazon Web Services for its serverless services AWS Lambda and AWS Fargate, since it is purpose-built for running serverless functions and containers safely and efficiently, and nothing more.

Worth mentioning

Unikernels

Unikernels (2013) are tiny virtual machines where a minimalistic operating system is linked directly with the target application. The resulting VM is typically only a few megabytes in size and can only run the target application.

The unikernel approach builds on past work in library OSs. The entire software stack of system libraries, language runtime, and applications is compiled into a single bootable VM image that runs directly on a standard hypervisor.

Many unikernel implementations, however, lack the maturity required for production platforms, e.g. missing the required tooling and a way for non-expert users to deploy custom images. This makes porting containerized applications very challenging. Container users also can rely on a large ecosystem of tools and support to run unmodified existing applications.

X-Containers (2019) is an alternative LibOS platform and improves container isolation based on paravirtualization, while providing isolation between containers. The X-Container platform automatically optimizes the binary of an application during runtime to improve performance by rewriting costly system calls into much cheaper function calls in the LibOS.

However, because of its architecture, it’s unsuitable for running some containers that still require process and kernel isolation. Also due to the requirement of running a LibOS with each container, X-Containers take longer time to boot and have bigger memory footprint.

WebAssembly

The aforementioned existing VM/container solutions are highly inefficient for enabling low latency functions and usage of the limited Edge resources.

The existing serverless frameworks host function instances in short-lived Virtual Machines (VMs) or containers, which support application process isolation and resource provisioning. These frameworks are heavy-weight for operating on Edge systems and not efficient for providing low latencies, especially when functions are instantiated for the first time (cold-start).

To achieve better efficiency, these platforms cache and reuse containers for multiple function calls within a given time window; e.g. 5 minutes, whereas some users send artificial requests to avoid container shutdown.

In the Edge environment, the long-lived and/or over-provisioned containers/VMs can quickly exhaust the limited node resources and become impractical for serving a large number of IoT devices. Therefore, supporting a high number of serverless functions while providing a low response time (say 10ms) is one of the main performance challenges for resource-constrained Edge computing nodes.

WebAssembly (Wasm), introduced in 2017, is a nascent technology that provides a strong memory isolation (through sandboxing) at near-native performance with a much smaller memory footprint. Engineers from the four major browser vendors (Google, Microsoft, Mozilla, Apple) have collaboratively designed a language to addresses the problem of safe, fast, portable low-level code on the Web.

The main storage of a WebAssembly program is a large array of bytes referred to as a linear memory or simply memory. All memory access is dynamically checked against the memory size and out of bounds access results in a trap. Linear memory is disjoint from code space, the execution stack, and the engine’s data structures; therefore compiled programs cannot corrupt their execution environment, jump to arbitrary locations, or perform other undefined behaviour. At worst, a buggy or exploited WebAssembly program can make a mess of the data in its own memory.

Wasm also enables the users to write functions in different languages, which are compiled into a platform-independent bytecode. Wasm runtimes have a power to leverage various hardware and software technologies for providing isolation and managing desirable resource allocations.

There has been a significant effort in the last years in adopting Wasm for a native execution, as it is a portable target for compilation of various high-level languages. Wasm standard does not necessarily make webspecific assumptions and there has been substantial work to standardize the WebAssembly System Interface (WASI) to run Wasm outside Web.

There are a number of Wasm runtimes for programs written in different languages, all focused on enabling the native execution of Wasm. In March 2019, the edge-computing platform Fastly has announced and open-sourced Lucet that provides a compiler and runtime to enable native execution of Wasm applications and can instantiate a Wasm module within 50μs, with just a few kilobytes of memory overhead.

WebAssembly could be then used as a new method for running serverless functions without the use of containers. This method leverages its binary format that provides inherent memory and execution safety guarantees via its language features and a runtime with strong sandboxing capabilities. This idea is still at its infancy but there has been some interest in the last year, as shown by the works done in “An Execution Model for Serverless Functions at the Edge (2019)” and “FAASM: Lightweight Isolation for Efficient Stateful Serverless Computing (2020)“.

References

- Blending Containers and Virtual Machines: A Study of Firecracker and gVisor. 2020.

- Challenges and Opportunities for Efficient Serverless Computing at the Edge. 2019

- FAASM: Lightweight Isolation for Efficient Stateful Serverless Computing. 2020

- Bringing the Web up to Speed with WebAssembly. 2017

- My VM is Lighter (and Safer) than your Container. 2017

- Unikernels: Library Operating Systems for the Cloud. 2013

- Virtual Machine Monitors: Current Technology and Future Trends. 2005.

- Containers and Cloud: From LXC to Docker to Kubernetes. 2014

- X-Containers: Breaking Down Barriers to Improve Performance and Isolation of Cloud-Native Containers. 2019